Lockdowns Had A Huge Impact On The Mental Health Of The Elderly

Ariadna Garcia-Prado, Universidad Pública de Navarra; Paula González, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, and Yolanda Rebollo Sanz, Universidad Pablo de Olavide

In Spain we suffered one of the strictest lockdowns in the world in response to the COVID pandemic. For a time, we were only allowed to go to the supermarket, the bank and the pharmacy. Children didn’t leave their homes for 58 days. Adults couldn’t go out for physical exercise, as it was the case in other countries. We had never faced a task as hard as this one before.

One of our friends called us almost every day, asking why children couldn’t go out and dogs could – animals’ owners could leave the house to walk them. Other days she questioned why we, the working age population, were not allowed to go to work. And she would get stressed, saying that we were going to go crazy locked up in small flats without terraces living 24 hours a day with our children. She was on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

She felt it made sense to isolate the older ones and those most vulnerable to the virus, but not everyone. She was not the only one who felt this way. In those days, videos of young people calling for the confinement of only the elderly were sent through instant messaging platforms. They were not very well received because they suggested it in a derogatory way. Could this really be an effective and, moreover, morally acceptable solution?

Why did mental health worsen?

Reports began to emerge that the mental health of the population had worsened markedly since the start of the pandemic, but there was little research into the causes of this. Was it due to the fear of illness and contagion, the resulting job instability, the overburdening of the health care system, or was it directly caused by confinement and social alienation?

As health economists, we felt it was our duty to deepen our understanding of this mental deterioration. And we decided to focus on the 50+ age group, for whom there were hardly any studies, despite the fact that the World Health Organisation considered this group to be highly vulnerable to social isolation.

Our data

To conduct the research, based on a sample of 40,501 individuals from 16 European countries and Israel, we combined three sources of data.

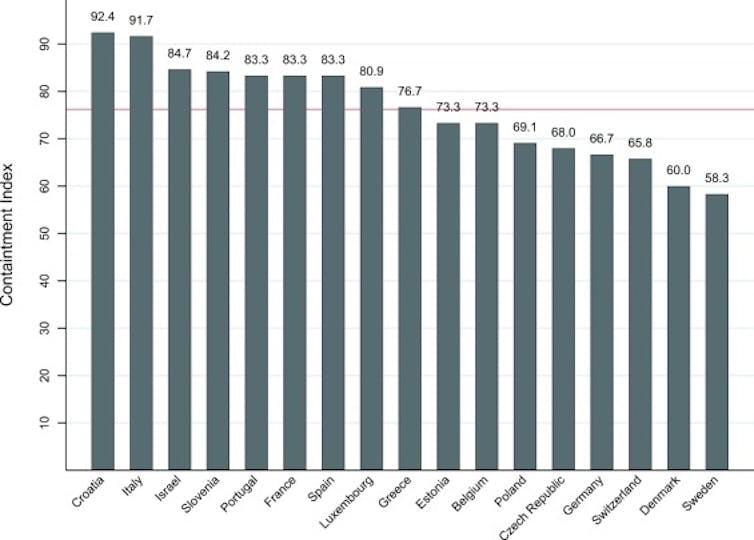

First, we used government indicators of pandemic response provided by the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. We focused exclusively on those indicators aimed at restricting mobility and social contact. In this way, we constructed an index that allowed us to rank the 17 countries according to the severity of the measures.

‘Lockdown strictness and mental health effects among older populations in Europe’. Economics & Human Biology. April, 2002.

Secondly, the COVID-19 questionnaire from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) allowed us to identify individuals who reported a worsening of their mental health after the outbreak of the pandemic.

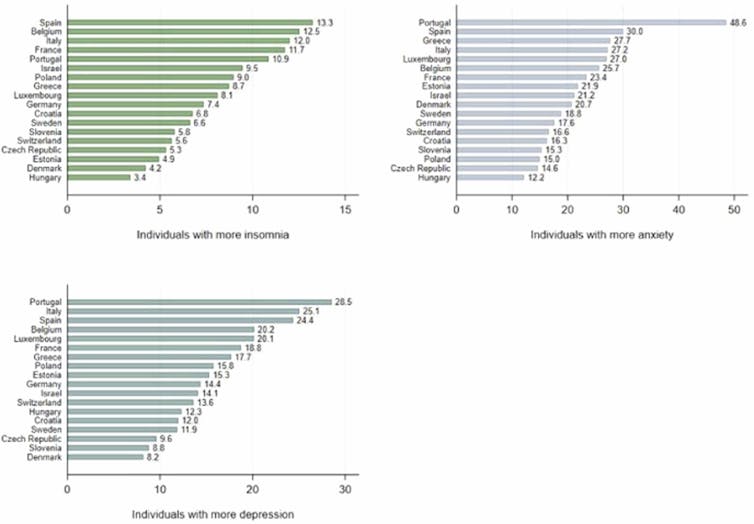

While on average insomnia increased for 9.9% of the respondents, this figure ranges from 4% in Denmark to more than three times that level in Spain (13%). A similarly broad range is found with the other two mental health outcomes. On average anxiety and depression increased by 23.1% and 18.7%, respectively, while figures range between 14.8% (Czech Republic) and 50% (Portugal) for anxiety, and from 8% (Denmark) to 28.9% (Portugal) for depression.

‘Lockdown strictness and mental health effects among older populations in Europe’. Economics & Human Biology. April, 2002.

Finally, we used the 2015 SHARE data to measure how often the over-50s interacted face-to-face before the pandemic.

Was confinement the cause of the decline?

We used a difference-in-difference model we felt could help us understand how much of the decline in the health of the older population in Europe was caused by the severity of mobility restrictions, rather than by other factors.

The results confirm that imposed isolation did indeed impair the mental health of the over-50s. Specifically, the incidence of insomnia, anxiety and depression increased by 74.6%, 39.5% and 36.4% respectively, as a direct consequence of strict confinement.

These figures do not change when we include other variables that may also affect mental health, such as exposure to the coronavirus of the individuals surveyed (eg. the number of close relatives infected) and the overall incidence of the disease in their countries of residence.

Women and the 50-65 age group were among the worst affected

It was also important to find out how confinement affected different subgroups of the population -according to gender, age, etc.- and we obtained four main results:

- Women were clearly the most adversely affected.

- Individuals who reported having good physical health before confinement were also more affected in their mental health.

- People aged 50 to 65 years suffered more deterioration, compared to those aged 65 to 75 years and those aged 75 years and over.

- Across all age and sex groups, individuals living alone were the most adversely affected by compulsory confinement.

Are selective confinements desirable?

Countries such as Spain and Italy considered the possibility of selective lockdowns and opted, in the end, to confine the entire population. Other countries, such as Turkey, Russia or the Philippines, only imposed solitary confinement on those over 65 years of age and/or those with health problems.

The results of our research suggest that it would be interesting, in the face of future pandemics, to adopt measures by population groups, confining older people who are in poorer health or more susceptible to serious illness. Moreover, as Daron Acemoglu, Victor Chernozhukov, Ivan Werning and Michael D. Whinston recently emphasised, selective confinement could alleviate the economic losses of locking the entire population in their homes.

So, after all, it seems that our friend was right: perhaps the best solution, both in economic and mental health terms, would have been to confine only the over-65s and the population most vulnerable to severe covid-19 illness. It is clear that for this type of measure to be morally acceptable, it must be accompanied by a good package of measures to support the mental health and psychosocial well-being of the confined group.![]()

Ariadna Garcia-Prado, Profesora Titular del Departamento de Economía (UPNA): Economía de la Salud; Economía de la Pobreza; Desarrollo Económico, Universidad Pública de Navarra; Paula González, Catedrática de Economía, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, and Yolanda Rebollo Sanz, Profesora Titular de Economia, Universidad Pablo de Olavide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Leave Comment: